2024 Asser Institute/OPCW WMD Training Programme on Disarmament and Non-Proliferation

Posted: May 28, 2024 Filed under: Nuclear Leave a commentThis announcement comes from my friend Thilo Marauhn:

2024 Asser Institute/OPCW WMD Training Programme on Disarmament and Non-Proliferation

The global non-proliferation norms regarding the use and proliferation of weapons of mass destruction are under pressure. The threat posed by nuclear, chemical and biological weapons has reached levels of urgency not seen since the Cold War. Consequently, there is a growing demand for professionals with the necessary legal, technical and policy expertise to tackle the challenges of today’s non-proliferation and disarmament agenda. Register now for the fifteenth training programme on disarmament and non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, co-organised with the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) on 30 September to 4 October 2024 in The Hague.

During this intensive training programme, you will receive a comprehensive overview of the international non-proliferation and disarmament framework. You will learn from renowned experts and practitioners in the field and engage in active discussions about key topics and current debates. The programme also provides you with the opportunity to build your professional network with experts in the field, as well as with your fellow participants.

Five full scholarships (tuition fee, international travel, accommodation and per diem) are available for candidates working in the field of WMD from Low/Lower Middle Income Economies of the World Bank. Deadline 23 June 2024.

Four tuition fee only scholarships are available for civil society representatives (including NGOs, think tanks, research or academic institutions). Deadline 23 July 2024.

New Article: Disarmament is Good, but What We Need Now is Arms Control

Posted: April 14, 2023 Filed under: Nuclear 1 CommentI wanted to post a link to my new article entitled Disarmament is Good, but What We Need Now is Arms Control.

It is currently posted to SSRN.

I wrote this piece to clarify what I perceive to be enduring and relevant confusion about the character and substance of treaties regulating nuclear weapons. Especially with the adoption of the TPNW, I find observers often misusing terms like disarmament, arms control, and nonproliferation as they apply to the obligations contained in nuclear weapons treaties. Especially now when New START, the last nuclear arms control treaty in force between the US and Russia is due to expire in 2026, and has already been suspended by Russia, it seems like a timely moment to clarify the character and role of nuclear weapons related treaties. In this piece I try to clearly lay out a taxonomy of legal obligations related to nuclear weapons in international treaties, and the relationships among those categories. I then examine the TPNW and consider how it should be understood to fit within this legal context. I conclude that, while the TPNW should be welcomed as a contribution to nuclear disarmament law, it should not be confused with nuclear arms control treaties which are distinct in role and purpose. The article concludes that at the current moment of crisis in nuclear arms control law, a refocusing of attention is needed to conclude a successor agreement or agreements following on to New START.

I hope you find it useful.

Dan

Russia’s apoplexy over biological research – Implications for the BTWC and its Articles V and VI

Posted: November 15, 2022 Filed under: Nuclear | Tags: biological weapons Leave a comment[Cross-posted from The Trench]

Since the summer, Russia has been adding chapters to the history of the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC) with its allegations of treaty violations against Ukraine and the USA. So far, it has culminated in convening a Formal Consultative Committee (FCM) under BTWC Article V in September and filing an Article VI complaint accompanied by a draft resolution proposing an investigative commission with the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) in October. The FCM was inconclusive because states parties reached no consensus on whether Moscow’s allegations have merit. Notwithstanding, a large majority of participating states rejected the accusations in their national statements. On 2 November, the draft resolution failed to garner sufficient votes.

Notwithstanding, both outcomes will impact the BTWC. The Ninth Review Conference will start in two weeks (28 November – 16 December). In their review of the articles, state parties will have to acknowledge the invocation of Articles V and VI. In the latter case, it was the first time in the BTWC’s 47 years. Finding consensus language reflecting the demarche may be problematic and could contribute to the review conference’s failure. In a statement after the UNSC vote on the draft resolution, the Russian delegate vowed that his country ‘will continue to further act within the framework of the [BTWC] and make the efforts needed to establish all of the facts having to do with the violations by the United States and Ukraine of their obligations under the Convention in the context of the activities of biological laboratories on the territory of Ukraine’.

At the same time, how Russia triggered Article VI and sought to establish an investigative committee and define its modalities elicited responses from UNSC members. These positions will likely influence discussions during and after the review conference whenever questions arise about the UNSC mandate and procedures in case of an Article VI complaint.

Getting to the UNSC

For years now, Russia has been complaining about US-funded biological research in former Soviet states. Russia’s campaign accusing Ukraine and the USA of running biological weapon (BW) activities in violation of the BTWC became more forceful in the months before it invaded Ukraine and an international issue afterwards. Having scurried through Ukrainian laboratories in occupied territory searching for incriminating evidence, Moscow compiled a dossier with documents and held press conferences to voice its allegations. It also convened three UNSC meetings in March and May. In this respect, it is interesting to note that Russia – a permanent member of the UNSC – buttresses its accusations with explicit references to so-called ‘evidence’ collected after occupying parts of Ukraine in blatant violation of the UN Charter. More specifically, Article 2(4) obliges UN members to ‘refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations’. In other words, by its admission, the evidence only became ‘available’ to Russia as a consequence of a significant crime against international law.

(Russian briefing on alleged Ukrainian BW activities)

Over the summer, Russia shifted into higher gear when it called for an FCM under BTWC Article V. This gathering ended without consensus on whether Russia’s claims were valid. However, an overwhelming majority of participating states rejected them as being meritless.

Dissatisfied again, Russia raised the matter once more before the First Committee of the UN General Assembly in October. It announced its preparation of a formal complaint under BTWC Article VI and an accompanying draft resolution to set up an investigative commission comprising all UNSC members. It lodged its complaint with the UNSC on 24 October.

Like at each of the previous UN meetings, the UN Office for Disarmament Affairs (UNODA) categorically stated that it had no evidence whatsoever that Ukraine was conducting biological research and development activities in violation of the BTWC. Moscow, however, dismissed those statements, arguing that UNODA based itself on Ukraine’s confidence-building declarations but is unable to verify their accuracy. In his right of reply towards the end of the UNSC meeting of 27 October, Russia’s Permanent Representative Vassily Nebenzia mocked UNODA’s capacity to collect relevant information.

Russia’s approach to triggering Article VI for the BTWC

On 24 October, Nebenzia addressed a letter to the President of the UNSC. It summarises Moscow’s grievances against Ukraine and the USA, reiterates outstanding questions after the FCM, and lodges a formal complaint with the UNSC under Article VI. The letter also has two annexes. The first one comprises lists of questions addressed to Ukraine and the USA and links to the working papers presented by Russia at the FCM. (The Russian letter of 24 October, which the UNSC president circulated in its original form – i.e. without a UNSC reference number – the next day, comprised 309 pages and included all the materials presented at press conferences and previous UNSC sessions.) The second one contains a draft resolution proposing the establishment of a commission consisting of all UNSC members to investigate its claims against Ukraine and the USA. As Nebenzia made clear during his statement to the UNSC on 27 October,

We also expect that the commission will present a relevant report on the issue containing recommendations to the Council no later than 30 November and inform the [BTWC] States parties of the results of the investigation at the Ninth Review Conference, to be held in Geneva from 28 November to 16 December.

Article VI (1) grants BTWC states parties the right to take a complaint to the UNSC. In terms of procedure, it only states that the complaint ‘should include all possible evidence confirming its validity’ and a ‘request for its consideration’ by the UNSC. The provision lacks guidance on the type of investigation the UNSC may initiate, and states parties have never elaborated investigation modalities. In the words of Director and Deputy to the High Representative for Disarmament Affairs Adedeji Ebo on 27 October:

The Convention does not provide any guidance on the type of investigation that the Council may initiate. States parties have also not developed any specific guidance or procedures concerning the modalities to be employed for the purposes of an article VI investigation. Should the Council initiate an investigation, the United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs stands ready to support it.

Put differently, a process to develop both mandate and procedures would have to precede a UNSC investigation in response to Russia’s complaint.

Neither the treaty text nor the common understandings reached at review conferences grant a complainant a right to propose the investigation’s mandate, the investigative team’s composition, and the time frame within which the team should report back. Russia thus not only triggered Article VI but also introduced a concurrent draft resolution determining the make-up of the investigative commission (experts from the current UNSC members, thus including Russia and the USA but excluding Ukraine) and setting a deadline for the investigative report (30 November 2022).

Did the UNSC veto the Russian draft resolution or not?

When put to the vote on 2 November, the UNSC did not adopt Russia’s draft resolution. The abstentions by all ten non-permanent members surprised: countries with outspoken views against Russia’s allegations, those that sought to balance their position with other geopolitical or economic interests, or the ones wishing to avoid setting precedents for Article VI in the absence of a majority behind Moscow’s proposal all adopted a common strategy. By denying the possibility of nine affirmative votes (as required by Article 27 of the UN Charter), they ensured rejection of the draft resolution irrespective of the permanent members’ actions. The five permanent members split, with China and Russia endorsing the proposal and France, the UK and USA rejecting it. The table below summarises the action by UNSC members (the linked document also contains each country’s justification of its vote).

| Votes in the UNSC on the Russian draft resolution | ||

| Yes | No | Abstain |

| China | France | Albania |

| Russian Federation | United Kingdom | Brazil |

| United States | Gabon | |

| Ghana | ||

| India | ||

| Ireland | ||

| Kenya | ||

| Mexico | ||

| Norway | ||

| United Arab Emirates |

Despite three permanent members’ rejecting the Russian draft resolution, their vote did not amount to a veto. This result suggests that the UNSC addressed a procedural matter rather than any ‘other matter’ (as stipulated in Article 27(3) of the UN Charter). The difference between both is that a procedural matter only needs nine affirmative votes, whereas any non-procedural matter requires nine affirmative votes, including the permanent members’ concurring votes. A procedural matter may pass despite a negative vote by one or more permanent members; a negative vote by a permanent member would defeat any ‘other matter’ of substance.

It is challenging to distinguish when the UNSC votes on a procedural or non-procedural matter because ‘most votes in the Council do not indicate by themselves whether the Council considers the matter voted upon as procedural or non-procedural’. However, the difference does become visible afterwards. The phrasing of the UNSC President’s statement of failure reveals the absence of vetoes in procedural matters:

- In a procedural matter, the announcement will include the phrase ‘… has not been adopted, having failed to obtain the required number of votes’.

- In all other matters, the standard phrase will be ‘… has not been adopted, owing to the negative vote of a permanent member of the Council’.

Thus the President (Ghana) announced the outcome as follows, thereby indicating that the vote was procedural:

The draft resolution received 2 votes in favour, 3 against and 10 abstentions.

The draft resolution has not been adopted, having failed to obtain the required number of votes.

We should add that had the UNSC adopted the Russian draft, the procedural nature of the vote would not have been outwardly apparent because the President would not have explained the result.

Consequences of the vote on the draft resolution

From the preceding, there is a clear need to distinguish between the formal complaint under Article VI and the accompanying draft resolution. With the latter, Russia used its position as a permanent UNSC member to undertake an action that is not available to any ‘ordinary’ BTWC state party (not seated in the UNSC). Earlier, we noted that Article VI(1) requires a state party to accompany the complaint with all relevant evidentiary materials and a request for the complaint’s consideration by the UNSC. Russia, however, phrased the request part differently (emphasis added):

In accordance with article VI of the Convention, the Russian Federation lodges to the Security Council a formal complaint, which includes all possible evidence confirming its validity, and reiterates its request to convene on 27 October 2022, in New York, a United Nations Security Council meeting to consider the attached draft resolution of the Council (see annex II).

Russia did not call for the UNSC’s consideration of the formal complaint. Instead, it requested a meeting to adopt the draft resolution. Given that the draft resolution called for establishing an investigative commission and designation of the current UNSC members as commission members, the proposal was a typical case for a procedural rather than substantive vote. In other words, the UNSC did not take up the matter of substance, namely the Article VI complaint. Had this been the case, France, the UK and USA would most likely have heard their opposition described as a ‘negative vote’.

Responses to the Russian complaint

The UNSC met twice after Russia had sent its letter invoking BTWC Article VI to the President on 27 October and 2 November. UNODA only spoke in the October meeting, reiterating that it had no information on illicit BW-related activities in Ukraine supported by the USA. In both instances, Russia was the first member to address the UNSC, during which it summarised its core allegations and the steps it had undertaken leading up to the triggering of the BTWC complaints procedure. It also presented the draft resolution on both occasions. In his statement on 27 October, Nebenzia introduced an element not featured in the letter to the President or the accompanying draft resolution. No Russian official seems to have repeated it since.

We have submitted a draft resolution to the Security Council. In accordance with article VI of the [BTWC], the draft is aimed at establishing and dispatching a Security Council commission to investigate into the claims against the United States and Ukraine […]

The reference to ‘dispatching’ is the only hint at onsite visits, possibly at an expert level in Ukraine. This activity would have raised the question of access to Ukrainian territory, especially those regions occupied by Russian forces. Without authorisation from Kyiv, a UN-mandated team cannot enter the Ukrainian territory as defined by its internationally recognised borders. (In March 1988, UN investigators could not travel to Halabja after Iraq’s chemical attacks against the city despite Iran’s control over large swaths of Iraqi Kurdistan.) An onsite visit to laboratories would also have raised serious issues about the forensic value of evidence collected in occupied Ukraine.

The draft resolution immediately became the subject of discussions at the expert level. An unofficial account has suggested that several UNSC members raised concerns about the investigative commission, mainly because of the absence of modalities for an Article VI complaint. While those countries did not reject the idea of an investigation outright, they were concerned that adopting the resolution would have precedent-setting implications for future UNSC-mandated investigations under Article VI. They, therefore, suggested that the draft text should include a precise mandate, structure and modalities for the commission. Russia reportedly did not consider the suggestion, maybe because its negotiation would considerably delay the resolution vote, making the finalisation of the investigative report before the end of November or the Ninth Review Conference mid-December all but impossible. Moscow’s apparent intransigence may have played a role in the non-permanent members’ abstention.

Three other principal factors may have also influenced their stance. First, UNODA’s repeated statements before the UNSC since March that it is not aware of any BW programmes in Ukraine, as alleged by Moscow, held strong sway over the representatives. The Russian delegation consequently faced a high barrier to arguing its allegations’ validity convincingly. In addition to the progressive loss of diplomatic clout over the war in Ukraine, the outcome of the FCM a mere two months before the UNSC vote added to Russia’s challenges of persuading the meeting. The outright, systematic refusal to accept any of the explanations offered by Ukraine and the USA also raised issues about Moscow’s motives behind the allegations.

Second, several UNSC members prized the quality of evidential materials. While Article VI(1) conditions UNSC action on a complaint including ‘all possible evidence confirming its validity’, states parties have never precised the nature of such proof. After their vote, several non-permanent members clarified that a complainant should not simply recycle evidence if it failed to convince the membership of another formal consultative body considering its allegations. Moscow had not only presented its accusations three times before to the UNSC, but it also called for an FCM during which it raised numerous questions and to which Ukraine and the USA answered in detail. While the substantive nature of the discussion in the FCM – in Nebenzia’s words – ‘confirm[s] the relevance of the problem that we raised’, the fact of the matter is that the gathering ended without a unanimous view. Consensus among nations when considering an international dispute sets an impossibly high bar. Still, in this instance, Russia only managed to convince a tiny coterie of satellite or aligned states of its case. In other words, if a BTWC state party triggers Article VI after unsuccessfully invoking Article V, UNSC members have now declared their expectation of substantial additional evidence before deciding on follow-on action.

Third, the USA especially argued that much of the assistance offered to Ukraine falls under BTWC Article X on assistance and cooperation on non-prohibited and other peaceful activities. Several countries belonging to the Global South voiced their concern that the accusations and proposed investigation without a proper mandate or procedures might delegitimise Article X projects.

Interventions by France, the UK and USA on 27 October and 2 November did not engage Russia on the substance of its allegations or merits of an investigative commission. Instead, they decried Russia’s political motives behind its manoeuvres, suggesting in passing that the country would never under any circumstances accept an evidence-based explanation of the biological research activities. In their mind, this also renders moot the idea of an investigative commission because Moscow would reject any finding that does not match its desired truth.

China finally voted in favour of the Russian draft resolution. It justified its stance by arguing that ‘the series of questions raised by Russia at the meeting were not fully answered’ during the FCM and therefore thought that Russia’s complaint to the UNSC and request to initiate an investigation were ‘reasonable and legitimate and should not be blocked’. It concluded ‘that a fair and transparent investigation by the Council can effectively address compliance concerns and help uphold the authority and effectiveness of the Convention’.

Despite its sustained declaratory support for President Vladimir Putin concerning Russia’s military operations in Syria and Ukraine, China is not Russia’s ally. Instead, it has interests that may be aligned with Moscow’s, particularly when countering Western and US influence in geopolitical and economic spheres. Reducing transparency about certain activities inside China, including ones that are subject to international oversight or verification (e.g. in terms of disarmament and arms control or incident notification), seems one part of the way Beijing presently aims to project itself on the world scene. Reading its statements on 27 October and 2 November carefully, it never endorsed Russia’s claims but couched its arguments to let procedures foreseen in the BTWC run their course. If adopted, Russia’s precedent-setting draft resolution would have given China a permanent place in the proposed investigative commission and hence a role in any investigation, including those called against it. The manner in which Beijing delayed investigations into the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic by the World Health Organisation, despite its reporting obligations under the International Health Regulations, blocked off access to the Wuhan Institute of Virology, or influenced report writing may be instructive in this respect.

In conclusion

Three issues stand out after the convening of the FCM and Russia’s invocation of Article VI, which BTWC states parties will have to consider during the forthcoming review conference:

First, in BTWC’s lifespan, Article V was invoked only twice: in 1997, after Cuba’s allegations that the USA had deliberately spread Thrips palmi insects over the island and last summer concerning Russia’s allegations of illicit biological research activities in Ukraine funded and controlled by the USA. In both instances, the FCM did not resolve the controversies for lack of consensus among the participating BTWC state parties.

This difficulty in reaching a consensus points to a fundamental flaw in the FCM design. As long as the accuser and the accused play their part in consensus building, the mechanism cannot arrive at a clear determination, one way or the other.

However, it is also an illusion that the Article V process might function effectively by excluding the adversary parties. To this end, BTWC states parties should be able to agree on a (reinforced) qualified majority vote and (ideally) inscribe in the procedure the expectation of state parties to accept the outcome of the vote.

After all, the outcome of such a vote is a collective judgement based on individual opinions by participating state parties, not a statement of fact. The truth is always political, not (necessarily) scientific. Russia, Iran and China have shown this principle time and time again by rejecting the scientific findings of the investigative teams of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) in Syria and accusing other members of politicising the OPCW’s work.

Second, Article VI has now been triggered for the first time. As the first paragraph stipulates: ‘Such a complaint should include all possible evidence confirming its validity, as well as a request for its consideration by the Security Council’. In this instance, Russia did not just file a complaint with the UNSC; it also used its status as a permanent member to simultaneously submit a draft resolution aiming to set up an investigative commission. The document also proposed specific modalities for that investigation, which BTWC states parties had not previously considered or agreed to.

As we noted earlier, the convention lacks a detailed procedure to trigger the provision. Because of the vote in the UNSC, proposals to enhance Article VI may now have to address whether a permanent member of the UNSC can submit a resolution proposal accompanying a complaint. In addition, they also have to determine whether a request to act on a concurrent draft resolution amounts to the request to have the complaint considered by the UNSC as explicitly stipulated in Article VI. The issue holds the potential of a consensus breaker at the review conference.

Finally, Russia resubmitted its previously circulated documentation whose value UNODA questioned four times (twice in March, May and October) when stating to the UNSC that it is unaware of the alleged BW programmes in Ukraine.

However one may interpret its outcome, the FCM did not conclude there were indications of a BTWC violation. Based on the national statements during the FCM, it is clear that an overwhelming majority of participating state parties did not accept Russia’s assertions. The question, therefore, arises whether Russia did not brutalise Article VI by submitting documents in evidence that the international community had already repeatedly judged as wanting.

State parties should stipulate that recirculated evidence cannot support an Article VI complaint if other formal consultative bodies have previously found such documentation inconclusive, deficient or insufficient.

To summarise, a sustained disinformation campaign highlights the BTWC’s weaknesses regarding verification and compliance. Article V may have some relevancy in conflict mitigation but cannot resolve allegations of breaches of the treaty unless the process is modified because of the experiences in 1997 and 2022. Russia’s invocation of Article VI using its position as a permanent member of the UNSC leads the BTWC into uncharted waters.

What Nuclear Weapons-Related Activities Are Covered by the Environmental Remediation obligation of the Nuclear Ban Treaty? Part 2: Policy Considerations and Ways Forward

Posted: June 25, 2022 Filed under: Nuclear 1 CommentBy: Dr. Christopher Evans

In the first part of this post, I discussed the lack of clarity concerning the scope of activities captured by the environmental remediation provision of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) contained in Article 6(2) based on an examination of this provision from a treaty interpretation perspective applying Articles 31 and 32 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. Having illustrated how continuing ambiguity exists, Part 2 of this post identifies certain policy/practical questions that states parties may wish to consider before deciding whether to endorse a broad or narrow interpretation of Article 6(2), and looks at some ‘ways forward’ whereby TPNW parties themselves could provide further clarification on this issue within the institutional settings of the first meeting of States parties (1MSP) of the TPNW.

Reinforce the humanitarian objectives of the TPNW?

To begin with, it could be argued that a broader interpretation of nuclear weapons-related activities covered under Article 6(2) would support the underlying humanitarian objectives of the treaty. Indeed, environmental remediation involves ‘measures that may be carried out to reduce the radiation exposure from existing contamination of land areas through actions applied to the contamination itself (the source) or to the exposure pathways to humans’ (here, page 28). As such, stepping beyond only the testing and use to address environmental harms caused by other nuclear weapons-related activities could positively impact human health and well-being by reducing sources of exposure. This would align with the TPNW’s overarching purpose as a ‘Humanitarian Disarmament’ treaty, which ‘focuses on preventing and remediating human suffering and environmental harm’ caused by problematic weapons, while equally remediating the environment as a specific objective.

At the same time, it may perhaps be worth recalling how environmental concerns have been framed previously in connection with nuclear weapons during the TPNW’s development process. For example, throughout the ‘Humanitarian Conferences on the Impact of Nuclear Weapons’ held in Oslo, Nayarit, and Vienna between March 2013–December 2014, most presentations stressed the devastating effects of past nuclear weapon testing and use for the environment, alongside the predicted environmental and climatic impact of any future use of nuclear weapons (see here, here, and here). Accordingly, a narrow interpretation of Article 6(2) would align with how environmental damage has previously been contextualised throughout the TPNW negotiation process, primarily in relation to the testing and use of nuclear weapons rather than additional activities.

Overburdening ‘Affected States parties’ under a broad interpretation?

A second issue is the need to display caution about creating overly arduous commitments under Article 6(2) upon TPNW parties. Indeed, as primary responsibility to implement Article 6 rests on ‘affected’ states parties rather than user/testing states (see here, pages 71-80 and here, pages 346-347), there remains a risk that affected states could be overburdened by the obligations under Article 6(2) if the phrase ‘activities relating to testing or use of nuclear weapons’ is interpreted broadly. To take one example, a state such as Kazakhstan, already heavily affected by former Soviet nuclear testing during the Cold War, would be required to extend its remediation efforts to cover its extensive uranium mining activities, not to mention other sources of contamination from the storage of nuclear weapons on Kazakh territory by the former Soviet Union. In essence, Kazakhstan would be ‘doubly’ affected by a broader interpretation of Article 6(2).

On the other hand, many others have only previously experienced a single, specific type of harm. For example, amongst current TPNW parties where uranium mining occurs including Namibia, and signatories like Niger, Malawi, no other significant ‘activities relating to the use or testing of nuclear weapons’ have previously taken place. Similarly, states that have been subjected to nuclear weapons testing, such as the Marshall Islands, Algeria, and Kiribati, do not also have a history of uranium mining or fissile material production. While this does not seek to downplay the challenges posed by remediating contaminated sites within these ‘singly’ affected states, it does indicate that resources will not always be overly stretched in every case if a broad interpretation of activities is endorsed by TPNW parties.

Finally, while Kazakhstan would be ‘doubly’ affected by a broader interpretation of Article 6(2), it nonetheless remained one of the few states that called for a broader range of activities to be addressed through environmental remediation at the 2017 negotiation conference (see here at 16:30-16:48). This may indicate that Kazakhstan is less concerned with the possibility or implications of becoming overburdened if Article 6(2) is extended broadly in the manner described.

Operational Challenges and Questions

RelatedLY, if a broad interpretation is endorsed, this could give rise to complex operational questions and challenges when implementing Article 6(2), particularly in terms of prioritising remediation efforts. For example, should affected parties address environmental damage from the testing and use of nuclear weapons and other related activities simultaneously, and thus divide their (often limited) resources? Alternatively, should environmental harms from a broader range of nuclear weapons-related activities could be addressed based in order of severity as opposed to the source of the harm? Or could a ‘stepped’ approach be adopted whereby contamination from past testing and use of nuclear weapons is addressed first, before attention turns to other sources of environmental damage? While a ‘stepped’ approach may prove a pragmatic solution, this prioritisation process could unintentionally create an implied ‘hierarchy’ of environmental harms, whereby the contamination from nuclear weapon testing and use are afforded priority over other, often equally devastating, forms of environmental damage (though equally, an implied hierarchy could arise under a narrow interpretation of activities captured by Article 6(2) by States parties, as this would reflect a conscious decision to address environmental harms solely from the use or testing of nuclear weapons above other sources).

Admittedly, these practical questions and concerns arising from how environmental harms under a broader interpretation of Article 6(2) would only arise in the case of States that are ‘doubly’ affected by various sources of nuclear weapons-related contamination that, as noted, may be the expectation rather than the norm. Moreover, it is worth noting that standards of best practice to assist with the remediation of contaminated areas following uranium mining, nuclear accidents, and other nuclear weapons-related forms of environmental harms have been developed by the International Atomic Energy Agency, and jointly by the Nuclear Energy Agency and the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Although these represent non-binding guidelines, this illustrates that affected states parties could use existing frameworks, guidance, and practices to address a wider range of nuclear weapons-related environmental harms if additional activities are caught by a broader interpretation of Article 6(2). Accordingly, while questions may arise in terms of prioritising sources of contamination to be addressed under a broader interpretation, existing standards of practice could help facilitate implementation of Article 6(2) on the ground.

Ways Forward

Given the inconclusiveness of the scope of activities captured by Article 6(2) after applying the rules of treaty interpretation, coupled with the above policy/practical questions identified, it is apparent that determining the precise scope of activities captured by Article 6(2) represents an important, though complex issue that requires further deliberation by TPNW parties. Because the operationalisation of Article 6 will likely constitute a high priority aspect of the TPNW for states parties (see generally the ‘Special Section’ of Volume 12(1) of Global Policy and here), it is recommended that this issue concerning the scope of nuclear weapons-related activities caught under Article 6(2) should form the basis of an agenda item to be considered further during (1MSP) established pursuant to Articles 8(1) and (2) scheduled to be held in Vienna between 21-23 June 2022.

In addition, it is suggested that 1MSP should establish an inter-sessional working group on this topic to provide TPNW parties and appropriate civil society and non-governmental organisations with an opportunity to advance positions on, and consider the implications of this issue more comprehensively. There have already been calls to create an inter-sessional working group in relation to the positive obligations under Article 6 generally, and this issue concerning the scope of activities caught by Article 6(2) could be situated within this, or its own, group.

In terms of composition, the inter-sessional working group should encourage participation from both ‘affected’ states and other TPNW parties that have prior experience in dealing with contamination from past nuclear weapons testing and use, nuclear-related accidents, or sources contamination caused by nuclear energy. Civil society, international organisations, engaged non-governmental organisations, and the academic and scientific community should also be permitted to participate in the discussions in order to provide valuable technical, scientific experience, and expertise on the wider challenges associated with environmental remediation (similar to the three Humanitarian Conferences and civil society input during the 2017 negotiation conference, see here page 108-109).

Finally, in terms of substantive outcomes of the inter-sessional working group, participating actors in the group could develop a draft discussion/issue paper to be shared at the next MSP. This may even advance some tentative recommendations as to how this ambiguity with Article 6(2) and the policy questions identified above could be addressed in due course. Such a broad composition, coupled with substantive outcomes, would allow participants in the inter-sessional working group to contribute substantively to discussions in order to resolve the ambiguity surrounding the phrase ‘activities related to the testing and use of nuclear weapons’ under Article 6(2).

Guest Post: What Nuclear Weapons-Related Activities Are Covered by the Environmental Remediation obligation of the Nuclear Ban Treaty? Part 1: A Question of Interpretation?

Posted: June 25, 2022 Filed under: Nuclear Leave a commentIn honor of the recently completed first meeting of state parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition on Nuclear Weapons, I’m pleased to host a two-part guest post by Dr. Christopher Evans. Chris is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in International Law at the University of Auckland. He completed his PhD at the University of Reading in February 2022, which received a full studentship from the AHRC South, West and Wales Doctoral Training Partnership. His research focuses on contemporary nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament law issues has been published in various journals and is available here.

———————————————————————————————————-

What Nuclear Weapons-Related Activities Are Covered by the Environmental Remediation obligation of the Nuclear Ban Treaty? Part 1: A Question of Interpretation?

By. Dr. Christopher Evans

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) TPNW represents a controversial development in nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament law that has been met with widespread opposition from the nuclear weapon-possessing states. Despite the fact that some commentators have questioned the contribution of the TPNW to nuclear disarmament efforts (see here and here), the forthcoming first meeting of states parties (1MSP) of the TPNW scheduled for 21-23 June 2022 constitutes the beginning of efforts to operationalise the ‘positive obligations’ contained in Article 6, which require affected states parties – rather than those states that had used or tested nuclear weapons (e.g. the nuclear weapon possessing states) – to address existing harms and damage to both affected individuals and the environment caused by the testing or use of nuclear weapons (see here, here, and here).

This two-part post examines a particular issue relating to the environmental remediation obligation established by Article 6(2) of the TPNW; specifically what nuclear weapons-related activities are covered by the remediation obligation imposed upon affected states parties under Article 6(2). In full, Article 6(2) reads:

‘Each State Party, with respect to areas under its jurisdiction or control contaminated as a result of activities related to the testing or use of nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices, shall take necessary and appropriate measures towards the environmental remediation of areas so contaminated.’

This two-part post explores this question from two perspectives. Part 1 first considers the scope of activities captured under Article 6(2) by employing the rules of treaty interpretation contained within Articles 31 and 32 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT) and which reflect customary international law (here, para. 99). Part 2 then identifies some policy/practical considerations stemming from a broad interpretation of Article 6(2), and provides some recommendations as to how states parties could proceed to clarify this question within the institutional framework of the TPNW.

A Matter of Interpretation?

As a first port of call, it is suggested that the scope of nuclear weapons-related activities captured by Article 6(2) could be interpreted either ‘narrowly’ to address only environmental contamination arising from the testing and use of nuclear weapons (see here, here, and here); or ‘broadly’ to capture additional activities ‘related to’ the nuclear weapons lifecycle, for example, uranium mining, fissile material production, and radioactive waste storage, each of which can cause environmental harm (see respectively, here, here, and here). Determining the scope of activities covered by the environmental remediation obligation in Article 6(2) rests on interpreting the provision in accordance with Articles 31 and 32 of the VCLT. Ultimately, however, it will be revealed that the application of treaty interpretation rules does not provide a clear answer as to whether a broad or narrow approach to the activities captured by Article 6(2) can be reached with any certainty.

Ordinary Meaning

Article 31(1) of the VCLT states that a treaty shall be interpreted ‘in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in light of its object and purpose’. Both the International Law Commission (here, page 220) and the International Court of Justice (here, para. 41) have emphasised that the ordinary meaning should be ‘starting point’ for interpretation and must be presumed ‘to be the authentic expression of the intentionof the parties’.

Applying this starting point, the ordinary language of Article 6(2) introduces the uncertainty surrounding the scope of activities covered. First, the fact that Article 6(2) only explicitly references nuclear weapons testing and use suggests that a narrower scope is implied. This view gains further support when one considers the comprehensive range of prohibitions included within Article 1. Indeed, as Article 1 forms part of the TPNW’s ‘context’ pursuant to Article 31(2) of the VCLT, the fact that only the use and testing of nuclear weapons are explicitly mentioned in Article 6(2) out of the comprehensive prohibitions established by Article 1 supports a narrow interpretation.

Furthermore, Article 6(2) contrasts with the comparable ‘Environmental Security’ provision of the 2006 Treaty on a Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone in Central Asia (Treaty of Semipalatinsk), where states parties undertake:

‘to assist any efforts toward the environmental rehabilitation of territories contaminated as a result of past activities related to the development, production or storage of nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices, in particular uranium tailings storage sites and nuclear test sites.’

Evidently, whereas the scope of activities captured by Article 6 of the Treaty of Semipalatinsk could be expanded without over-extending the ordinary language of the provision, such a broader interpretation would be more difficult to reconcile with Article 6(2) of the TPNW, which instead refers only to nuclear weapons testing and use.

Nevertheless, the inclusion of the preceding phrase ‘activities related to…’ does seem indicate a broader scope that would encompass additional activities that are closely connected to either nuclear weapons use or testing. Indeed, some commentators have suggested that Article 6(2) ‘covers contamination resulting from, for example, production, transport or stockpiling of nuclear weapons, as these are “activities related to” testing and use’ (here page 9). Moffatt has likewise argued:

‘it may seem arguable to perhaps interpret Article 6(2) as requiring environmental remediation of areas where activities such as mining, milling or disposal have taken place, those activities have in fact resulted in contamination and these activities were exclusively performed not for peaceful purposes, but only “related to […] testing or use”.’ (page 39).

Moreover, when one considers the entirety of Article 6, paragraph 1 addressing victim assistance only refers to ‘individuals under its jurisdiction who are affected by the use or testing of nuclear weapon’, thus omitting the preceding phrase ‘activities related to’. This could suggests that whereas victim assistance should be provided more limitedly to individuals affected specifically by the testing or use of nuclear weapons, Article 6(2) has a broader ambit capturing additional activities related to testing and use. At the same time, however, if participating states desired a broader range of activities to be covered under Article 6(2), it is unclear why additional activities were not expressly incorporated in the text in a similar manner to the language adopted by the Treaty of Semipalatinsk.

For the above reasons, therefore, it seems the ordinary meaning fails to clarify the scope of activities requiring environmental remediation under Article 6(2).

Negotiation History

This ambiguity means that it is necessary to examine whether the negotiation history (travaux préparatoires) of the TPNW during the 2017 negotiation conference (2017 Conference) can shed any further light on the scope of Article 6(2). Under Article 32 of the VCLT, recourse to the travaux préparatoires is permissible when the interpretation under Article 31 of the VCLT either a) ‘leaves the meaning ambiguous or obscure’; or b) ‘leads to a result which is manifestly absurd or unreasonable’. Again, however, the travaux préparatoires offers little assistance in clarifying the scope of activities captured by Article 6(2).

According to Pace University, ‘16 states plus CARICOM expressed support in their statements for environmental remediation of areas contaminated by the use (including testing) of nuclear weapons’ during the March 2017 session (para. 9). Other participants, called for a broader range of nuclear weapons-related activities to be explicitly included in any environmental remediation obligation established. Papua New Guinea, for instance, suggested that the phrase ‘activities related to the use, testing, production or storage of nuclear weapons in their territory’ could be included in connection with environmental remediation (para. 9). Civil society too argued for a broader scope. For example, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom argued that:

‘The ban treaty should reflect the need to rehabilitate territories that have been contaminated as a result of activities related to the use, development, testing, production, transit, transshipment, or storage of nuclear weapons in their territory.’ (para. 5).

Facing these differing viewpoints, conference President Whyte Gómez included an environmental remediation provision in the initial Draft Convention released on 22 May 2017, which read as follows

‘Each State Party with respect to areas under its jurisdiction or control contaminated as a result of activities related to the testing or use of nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices, shall have the right to request and to receive assistance toward the environmental remediation of areas so contaminated.’

Accordingly, despite proposals to explicitly include additional nuclear weapons-related activities in the March 2017 session, no such language was included in the 22 May Draft. This draft environmental remediation provision was not discussed again until the 17th plenary session held on 20 June 2017, though no participating state sought to clarify the meaning of the phrase ‘contaminated as a result of activities related to the testing or use of nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices’.

Following the 20 June 2017 plenary session, further consideration of Article 6 shifted to behind closed doors negotiations facilitated by Ambassador Labbé of Chile. Although no public records of the discussions are available, the final recommendations adopted by Ambassador Labbé on 30 June 2017 did not expand or clarify the meaning of the phrase ‘activities related to the testing and use of nuclear weapons’. This is despite suggestions by the International Association of Lawyers Against Nuclear Arms (para. 9) and the Italian branch of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (para. 14) to include the ‘production’ stage of nuclear weapons in both the victim assistance and environmental remediation obligations.

However, on 5July 2017, during the final stages of the negotiations, Kazakhstan suggested adopting the phrase ‘past activities associated with the development, production, storage of nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices, for instance uranium tailings’ within Article 6 generally (see here at 16:30-16:48). While this represented a last-ditch attempt to expand the range of nuclear weapons-related activities captured under Article 6, the limited remaining mandated time meant that other issues required more urgent discussion, notably disagreement on the primary/fundamental responsibility of user states for implementing the positive obligations. Accordingly, the text complied by the informal group on 30 June 2017 remained unchanged, while the scope of the phrase ‘activities related to the use or testing of nuclear weapons’ remained unelaborated and unaddressed.

Summary

Overall, the application of Articles 31 and 32 of the VCLT does not provide any decisive clarification on the scope of activities covered under Article 6(2), suggesting in turn that either a narrow or broad interpretation could be endorsed by States in the future. Part 2 of this blog turns to consider various policy and practical considerations arising from both a broad and narrow interpretation of activities captured by Article 6(2), and provide some suggestions on how to address this ambiguity within the framework of the TPNW.

Podcast on AUKUS

Posted: June 12, 2022 Filed under: Nuclear 2 CommentsI wanted to post a podcast I was recently invited to do by my friend, Professor Don Rothwell of the Australian National University. We actually recorded it back in December 2021, but the legal issues haven’t significantly changed. I’m guest teaching a course right now at the ANU on Nuclear Security Law, and it brought this podcast back to mind. Anyway, it’s not long – only about 18 minutes. Enjoy!

Rothwell/Joyner Interview on AUKUS

Increasing assurance under the BTWC through biorisk management standards

Posted: November 2, 2020 Filed under: Biological | Tags: Belgium, Biorisk management, Biosecurity, BTWC, European Union, Kazakhstan, Verification Leave a comment[Cross-posted from The Trench]

The final report of the 7th Review Conference of the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC) held in December 2011 contained a one-line subparagraph whose ambition came to fruition in December 2019. Under Article IV (on national implementation measures), paragraph 13 opened as follows:

The Conference notes the value of national implementation measures, as appropriate, in accordance with the constitutional process of each State Party, to:

(a) implement voluntary management standards on biosafety and biosecurity;

That single line of new language in the final report was the outcome of a preparatory process that had begun in September 2009 and led to a Belgian Review Conference working paper endorsed by the European Union (EU). Prompted by the final report’s language, the International Organisation for Standards (ISO) initiated the complex procedure for developing a new standard. Just over seven years after the 7th Review Conference, it published the new standard, ISO 35001:2019 Biorisk management for laboratories and other related organisations.

Today, amid the global pandemic caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), questions about the virus’s origins abound. Might it have escaped from a high-containment laboratory? Did the epidemic result from a deliberate release? While we can source most of these claims to conspiracy theorists and wilful disinformation propagators, the clampdown of Chinese bureaucracy on early outbreak reports, the government’s failure to immediately report the emerging epidemic to the World Health Organisation (WHO), and its subsequent extreme vetting of any scientific publication discussing COVID-19’s origins created the space for the wildest stories to flourish.

Over the next months and years researchers from many disciplines will analyse the response by the WHO and the adequacy of the outbreak reporting requirements under the International Health Regulations. Even though nothing suggests that COVID-19 resulted from a deliberate release of a pathogen or that the virus was artificially created or genetically altered in a laboratory, different aspects of the BTWC regime relate to the reporting of outbreaks, biosecurity and -safety in laboratories and other installations, and international cooperation.

Interesting in this respect is whether the new ISO standard offers opportunities to reinforce the BTWC. In preparation for the 2020 BTWC Meetings of Experts (MX), to be held exceptionally in December instead of the late summer due to COVID-19 meeting restrictions at the United Nations, Belgium with Austria. Chile, France, Germany, Iraq, Ireland, Netherlands, Spain and Thailand submitted a working paper entitled ‘Biorisk management standards and their role in BTWC implementation’ (BWC/MSP/2020/MX.2/WP.2, 27 October2020).

Early genesis of a small success

September 2009. I was a disarmament researcher at the Paris-based European Union Institute for Security Studies (EU-ISS). The 7th BTWC Review Conference was just over two years away. I met with an acquaintance from my days at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) and a senior official at the Foreign Ministry in Brussels. I had a straightforward question for them. Belgium would hold the 6-monthly rotating Presidency of the European Council during the second half of 2010. A year before the Review Conference, this was the ideal time to update the EU Common Position for the quinquennial meeting.

Holding the Presidency offers plenty of opportunities for initiative. In 2009 EU members had no specific plans to update their common position. The 6th Review Conference they considered a success (which was relative considering the disaster five years earlier). Three months after the meeting in Brussels, the Belgian Foreign Ministry decided to seek an updated EU position. Preparations already began under the Swedish Presidency during the first half of 2010.

The idea I had put forward in Brussels was maximalist: how to equip the BTWC with verification tools? I was not seeking to reopen the Ad Hoc Group (AHG) negotiations the United States had aborted in 2001 because by the turn of the century I had already come to the conclusion that the tools under consideration in Geneva addressed past problems and not the most recent developments in biology and biotechnology. Many academics observing the AHG deliberations recognised the shortcomings of the draft text but pushed for completing the draft protocol to the BTWC, fearing that the proceedings were losing momentum. However, their argument that the protocol could be amended afterwards I did not share. In my mind, a return to the design board was the only option.

On the way to a national and common EU position

On 18 May 2010, during the Swedish Presidency, the EU Council’s Working Party on Global Disarmament and Arms Control (CODUN) invited me to present my thoughts on how to strengthen the BTWC. CODUN coordinated the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy regarding global disarmament and UN-related issues, which included the BTWC. (CODUN has since then been absorbed into the Working Party on Non-proliferation – CONOP.) In the EU-ISS note prepared for the briefing I identified five areas of possible progress on verification-related questions: (1) industry verification; (2) biodefence programmes; (3) technology transfers; (4) allegations of BW use and unusual outbreaks of disease; and (5) countering BW threats posed by terrorist and criminal entities. I added the following caveat:

Under the present circumstances it does not appear feasible to consider the five areas in a single, holistic model for a future BTWC. New, non-state actors have risen to prominence in the disarmament debate (the industry, scientific and professional communities, but also terrorist and criminal entities). There are different challenges posed by rapid advances in science, technology and processes that may contribute to BW acquisition, the major changes in the international security environment over the past three decades (and since the 9/11 attacks and the invasion of Iraq in particular) and the resulting changes in security expectations from weapon control treaties and their verification tools.

The main aim for the EU, I suggested, was to

obtain a decision at the 7th Review Conference establishing one or more working groups to explore and identify novel approaches to verifying the BTWC. These working groups are to meet several times during the next intersessional period and report to the 8th Review Conference in 2016, at which point States Parties may decide to act on the findings.

Critical elements in the deliberations will be: (1) the building and application of the principle of multi-stakeholdership, with direct participation of the industrial and scientific communities; (2) the identification of processes and technologies to support the verification goals, and, where required, to identify such processes and technologies that need to be created and developed based on the latest scientific and technological advances, e.g., in detection or biological forensics; and (3) for the EU, to actively support the process by taking the lead in testing the proposed verification methodologies in realistic settings with a view of both ascertaining their feasibleness and finetuning the proposals.

The latter element was critical for deliberations to move from the conceptual to the practical. In a footnote, I clarified:

This aspect is particularly important with respect to the design and implementation of novel verification principles, techniques and technologies. For example, before the signing of the 1987 Treaty on the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) the United States and the Soviet Union had conducted over 400 trial inspections. The goals of those trials included the testing of the concept of onsite inspection, the finetuning of verification requirements and the investigation of ways in which sensitive information could be protected without undermining the stated verification goals.

The remainder of the note addressed the five issue areas. The document ended with a separate section on stakeholders and their involvement in verification, which included arguments to have industry and the scientific communities engaged in the preparatory processes.

Sharpening the focus

Read the rest of this entry »Biological weapons: A surprise proposal from Kazakhstan worth exploring

Posted: October 6, 2020 Filed under: Biological | Tags: BTWC, CBM, Compliance, Disarmament, Emergency assistance, Investigation of use, Kazakhstan, Verification 2 CommentsThis year the UN General Assembly (UNGA) celebrates the 75th time in session. However, the worldwide spread of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) casts dark shadow over the anniversary with some of the major global players preferring to play geopolitics when nations should unite to combat a germ that knows no borders.

Unsurprisingly, many heads of state or government, ministers and other dignitaries have reflected in their statements on the pandemic and the challenges ahead. Some introduced constructive suggestions to address the factors that led to the outbreak at the end of last year. Others put forward ideas to strengthen crisis response and management capacities.

Among these, Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev in his address on 23 September launched the surprising proposal to

‘establish a special multilateral body – the International Agency for Biological Safety – based on the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention and accountable to the UN Security Council’.

His reference to the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC) in the broader context of public health is noteworthy. It was one of five ideas to combat the pandemic, the other four being the upgrading of national health institutions; the removal of politics out of the vaccine; the revision of the International Health Regulations to increase capacities of the World Health Organisation (WHO); and the examination of the idea of a network of Regional Centres for Disease Control and Biosafety under the UN auspices.

Given the many accusations that the virus is human-made, escaped from a laboratory or was part of a biological weapon (BW) programme and the ease with which disinformation circulates through the social media, an initiative that relies on the BTWC makes sense. After all, the convention deals with questions of non-compliance or accusations of biological warfare.

What does the proposal entail?

No further details about the International Agency for Biological Safety (IABS) are available from Kazakh missions. This leaves us with few clues about its purpose, structure and way of functioning.

- As an ‘agency’, the IABS would presumably be department or administrative unit of a bigger entity. Because it would be accountable to the UN Security Council (UNSC) Kazakhstan probably envisages it as a UN subsidiary body. In one sense, the organ could be a relatively autonomous structure (e.g. under a Commissioner-General) set up by the UNGA. However, the sole reference to the UNSC appears at odds with a UNGA subsidiary body.

- However, the characterisation of the body as ‘multilateral’ indicates that states – whether parties to the BTWC or UN members is unspecified – might govern the agency rather than a bureaucratic entity such as the UN. In this understanding, the reference might be to a UN specialised agency (an autonomous organisation integrated by agreement into the UN system, e.g. the WHO) or a related organisation that by agreement reports to the UNGA and UNSC, similar to the International Atomic Energy Agency and the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. This interpretation, however, does not sit well with ‘ accountability’ to the UNSC and lack of reference to the UNGA.

- The organ is about biological safety, therefore presumably about handling dangerous pathogens. If the Kazakh language does not differentiate between ‘biosafety’ and ‘biosecurity’ (Google Translate renders both terms as ‘биоқауіпсіздік’ [bïoqawipsizdik]), then preventing pathogens from escaping high-containment facilities may also fall within the agency’s purview.

- Finally, the BTWC reference suggests that the agency would address questions not usually within the remit of the WHO, i.e. research and development that may lead to BW or biodefence programmes.

How about the IABS in the BTWC context?

According to the Kazakh proposal the IABS should be based on the BTWC. The preposition ‘on’ could mean that the scope of its mandate equals that of the disarmament treaty or that it should work supporting BTWC objectives.

As is well known, the BTWC has no formal institutional setup in which the body might be integrated. Yet is it too wild an idea to link it to the Implementation Support Unit (ISU)? Even while ownership of the treaty lies with the states parties, they have embedded the ISU within the UN Office for Disarmament Affairs (UNODA). In that option, the IABS might meet the twin criteria of being an agency and multilateral put forward by Kazakhstan.

However, the ISU is not a formal administrative entity within UNODA or the UN. Its continued existence depends on the BTWC states parties, who must renew its mandate and adopt a budget for the next five years at review conferences. For the IABS they would thus also have to decide on staffing levels and a budget based on a pre-agreed mandate. Similar types of consideration await proposals to establish a scientific advisory body for the BTWC. Therefore, for the IABS an additional key decision will be whether it becomes part of the ISU or functions separately within UNODA.

How could IABS support the BTWC objectives?

There is little purpose in debating possible structures without a sense of possible IABS roles. The IABS may conceivably support the BTWC objectives in two areas, namely regarding confidence building measures (CBMs) and Article VII on emergency assistance.

Enhancement of CBM utility

Because of the presentation of the proposal in the context of the pandemic, the IABS could focus on CBM B ‘Exchange of information on outbreaks of infectious diseases and similar occurrences caused by toxins’.

CBMs are submitted annually with a formal deadline on 15 April. Consequently, outbreaks cover the past year, and the process does not inform states parties at when the incident occurs. Moreover, the process is passive. States parties receive the information in at least one of the six official UN languages but many lack the resources to translate the documents or the capacity to analyse them in depth.

A process can be envisaged whereby states parties submit to the IABS when possible details of a unusual disease outbreaks with additional information as to whether this unusual outbreak is natural, accidental or believed to be deliberate. A state party could conceivably notify the agency of any outbreak about which it has information. The IABS processes this information and provides it to all states parties within the shortest possible delays. Any state party can follow up through bilateral consultations or may offer specific types of assistance to address the outbreak. Another advantage of such a process would be the early squashing of conspiracy theories.

One could envisage that the IABS also acts as an interface for CBM A, Parts 1 and 2, respectively on ‘Exchange of data on research centres and laboratories’ and ‘Exchange of information on national biological defence research and development programmes’. As noted earlier, biosafety and -security would be at the heart of the agency.

In this way, a passive CBM process could be elevated to an active assurance strategy whereby states parties commit themselves to be transparent about unusual disease outbreaks. Failure to report or late reporting of such an outbreak or accident could give other states parties cause to seek clarification, more so as it not usually possible to hide such an event.

While cooperation with the WHO and other international health organisations for human, animal and plant diseases would most likely emerge, the principal focus of the IABS would be defined by the BTWC: prevention of BWs and their use.

Focal point for Article VII

In view of the possible roles outlined above, it seems a natural next step to envisage the IABS as a focal point for requesting emergency assistance under Article VII if a state party has been exposed to a danger because of a violation of the BTWC.

There is no procedure foreseen for a state wishing to invoke the provision. Tabletop exercises run between 2016 and 2019 have shown that participants hesitate to activate the article. Such a step automatically implies a violation of the BTWC and may escalate a conflict. Furthermore, there are questions about what type of evidence the requesting state party must supply and the role of the other states parties in the process given the involvement of the UNSC. In addition, the outbreak will be noted a while before first suspicions of deliberate intent arise.

As the IABS would have been informed of the outbreak early on, a state party believing it has been exposed to a danger resulting from a breach of the BTWC could submit its evidence for further consideration. Clarification processes may alleviate concerns or give cause to forward the matter to the UNSC. In any case, having an agency such as the IABS would hand states parties a tool and an opportunity to be seized by the matter without having to set up a lengthy preparatory process for consultations under BTWC Article V.

Concluding thoughts

For sure, some further elaboration of the IABS idea by the Kazakh government would be great, e.g. in a working paper for the BTWC meeting of experts in December (having been postponed as a consequences of the pandemic) or the review conference next year.

Kazakhstan should also clarify its understanding of the phrase ‘accountable to the UN Security Council’. In several articles the BTWC refers to roles to be played by the UNSC. However, these are often seen as an impediment to activating the relevant provision because decisions or actions by the UNSC are unpredictable in their outcome.

Notwithstanding, the Kazakh proposal already tantalises as it is. As an agency it might fulfil useful tasks at relatively small cost in areas of concern to states parties. The discussion, if not accusations about the origins of SARS-CoV-2 show that something substantive is lacking in the international security machinery to generate transparency and confidence in the accuracy of information.

Looking forward to more ideas and discussions.

History of nerve agent assassinations

Posted: September 9, 2020 Filed under: Chemical | Tags: Assassination, Japan, Nerve agent, Novichok, Russia, Terrorism 8 Comments[Cross-posted from The Trench]

On 20 August, the Russian anti-corruption activist Alexei Navalny fell ill during a return flight to Moscow and was hospitalised in the Siberian town of Omsk after an emergency landing. Members of his travelling party immediately suspected poisoning, an impression hospital staff reinforced when they refused Navalny’s personal physician access to his medical records.

Following his airlifting to Berlin for further examination and specialist treatment, the Charité hospital issued a statement on 24 August that preliminary findings indicated exposure to ‘a substance from the group of cholinesterase inhibitors’. Even though the hospital could then not name the specific poison used, it added that multiple tests by independent laboratories had confirmed the effect of the poison. The hospital was also treating him with the antidote atropine. The references to a cholinesterase inhibitor and atropine were the first strong indicators of a neurotoxicant, to which nerve agents like sarin, VX or the novichoks belong.

A week later, on 2 September, German Chancellor Angela Merkel confirmed the assassination attempt with a novichok agent at a press conference. She drew on the conclusions from biomedical analyses by the Institut für Pharmakologie und Toxikologie der Bundeswehr (Bundeswehr Institute of Pharmacology and Toxicology), one of the top laboratories designated by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons to investigate biomedical samples.

From natural poisons to warfare agents

Poisoning political opponents or enemies is not new. In his almost 600 pages-long ‘Die Gifte in der Weltgeschichte’ (1920) the German pharmacologist Louis Lewin detailed chapter after chapter how besides criminals and spurned lovers, rulers, leaders, undercover agents and conspirators applied the most noxious substances in pursuing domestic political or international geopolitical objectives. Reviews of chemical and biological weapons (CBW) usage through the 20th century similarly list successful and attempted assassinations with mineral poisons or animal and plant toxins in and outside of war.

Modern chemical weapons (CW) – typically human-made toxic compounds standardised for use on battlefields – have rarely been selected to target individuals. Observers and journalists reported first use of nerve agents by Iraq against Iran in 1983, almost five decades after their initial discovery in Nazi Germany. In March 1995 the world learned of Aum Shinrikyo after its members had released the nerve agent sarin in the Tokyo underground. However, during the previous eight months the extremist cult had also resorted to both sarin and VX in attempts to assassinate judges about to rule against Aum Shinrikyo and individuals who posed a threat or had defected from the religious group. These were the first and for more than a decade and a half the only reports of neurotoxicants used to murder individuals.

The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) eliminated Kim Jong-nam, half-brother of North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, with a binary form of VX in February 2017. Just over a year later, in March 2018, Russian operatives attempted to murder a former double agent Sergei Skripal in Salisbury, UK with a nerve agent belonging to the lesser known family of so-called ‘novichoks’ (newcomer). Skripal’s daughter and a police officer were also exposed to the toxicant. They too survived. In June two British citizens fell ill in the nearby town of Amesbury because of exposure to the agent in a small bottle discarded by the Russian agents. One exposed person succumbed.

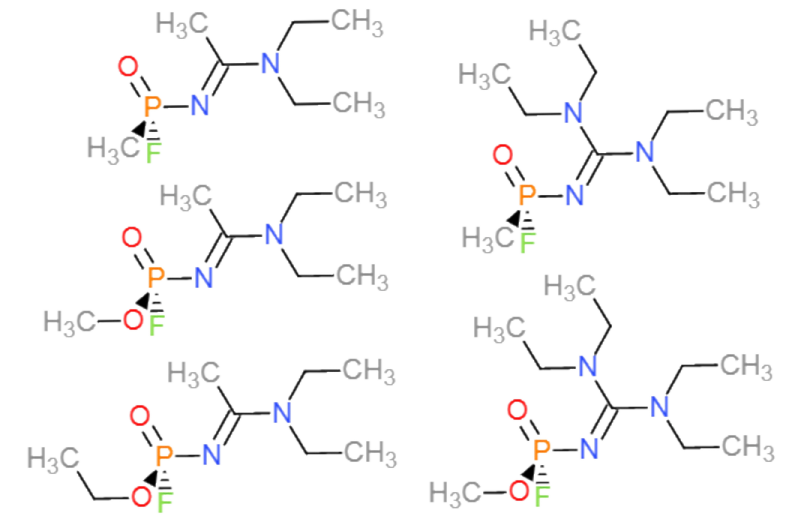

Novichok family of nerve agents (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Following the Skripal case the Bulgarian Prosecutor General reopened a poisoning case in October 2018 at the request of the victim, arms manufacturer and trader Emilian Gebrev. The assassination attempt dated to April 2015. Also exposed were his son and the production manager of the Dunarit munitions factory. The Prosecutor General confirmed that a Russian operative linked to the Skripal attempt had visited Bulgaria at the time of the incident. Subsequent forensic analysis of serum and urine samples from Gebrev by the Finnish laboratory VERIFIN confirmed the poisoning. According to the UK-based CW expert Dan Kaszeta, who read a copy of the report, the Finnish institute intimated that Gebrev might have been exposed to an organophosphate pesticide. A Bulgarian news outlet has suggested the agricultural insecticide Amiton (also known as Tetram). Now commercially banned because of its high toxicity, in the 1950s the UK investigated its use as a nerve agent under the code VG.

Some reports have also claimed that Aum Shinrikyo murdered around 20 dissident members and defectors with VX in one of the cult’s compounds. To the best of my knowledge no documentary evidence to support the claim has been published.

Previous assassination operations involving nerve agents

Nerve agents were battlefield weapons, mostly liquids of different viscosity. The volatile sarin could prepare the pathway of an attack, whereas the oilier tabun and VX had their greatest utility as area denial weapons for defending terrain or protecting flanks during an advance. Their manufacture in large volumes is complex and maintaining their stability during longer-term storage is a hurdle that even few states have satisfactorily crossed. In laboratory volumes, a skilled chemist may be able to synthesise agent of high purity. But this person would have to take the greatest precautions to avoid inadvertent exposure to its noxious properties. While the relatively high toxicity of nerve agents may appear attractive to terrorists or assassins, the marginal benefit they offer over other terrorist or criminal tools is usually too small to make the investments or risks worthwhile. Hence, their use by terrorists or criminals has been rare.

Until recently, their use in assassination operations would have been considered even rarer, especially because of the poor results obtained by the Japanese cult Aum Shinrikyo in the first half of the 1990s.

The following table summarises known assassination operations with neurotoxicants.

| Date | Perpetrator | Comments |

| 27 June 1994 | Aum Shinrikyo | Sarin released in Matsumoto from a converted lorry to kill three judges who were to rule in a land dispute. They survived. However, the drifting sarin cloud eventually killed eight persons and injured over 500. |

| Autumn 1994 | Aum Shinrikyo | Suspected VX attack against Taro Takimoto, lawyer for Aum victims. The agent had been applied on the handle of his car door. Failed, reasons unknown |

| Autumn 1994 | Aum Shinrikyo | Second suspected VX attack against Taro Takimoto. The agent had been inserted into a keyhole. Failed, reasons unknown. (Aum reportedly also attempted to murder this person with botulinum toxin around this time.) |

| 28 November 1994 | Aum Shinrikyo | VX squirted from a syringe onto Noboru Mizonu in retaliation for offering shelter to former Aum members. Failed. |

| 2 December 1994 | Aum Shinrikyo | Second attack on Noboru Mizonu with VX delivered drop by drop from a syringe. Hospitalisation for 45 days required. |

| 12 December 1994 | Aum Shinrikyo | VX injected with a syringe into Tadahito Hamaguchi in Osaka, having been misidentified as a police spy. First person ever to have been deliberately killed with VX. |

| 4 January 1995 | Aum Shinrikyo | VX syringe attack against the head of the Aum Victims Society, Hiroyuki Nagaoka. Hospitalised for several weeks. |

| 28 April 2015 | Russia | Bulgarian arms trader Emilian Gebrev poisoned with an organophosphorus compound. Two other persons present also suffered consequences. Following the Skripal case in March 2018, a possible link to novichok has been suggested but not confirmed. Bulgaria charged three Russian operatives with attempted murder in January 2020, one of whom is also a suspect in the Skripal case. |